The 'original' censored Bond books

- Peter Crush

- Aug 31, 2025

- 10 min read

Long before the latest James Bond reprints had some 'sensitivity reader' changes made to them, seven of the original Bond books were edited down, specifically as children's editions - despite Fleming saying he didn't write for kids:

It’s not often I use this channel to plug a specific book, or set of books, but in this week’s blog I’m going to be making a rare exception.

That’s because I’ve recently completed pulling together a difficult set of Fleming paperbacks to find (another deviation from the norm!) – and they’re a set that are quite significantly different to the norm.

They’re not UK Pan or US Signet first printings, but comprise a collection that, despite only running to seven of the 14 books, are nevertheless without compare.

This is because they are the so-called ‘Bulls-eye’ (see logos) books - and specifically children’s adaptations of some of the key James Bond novels.

The full set of these superb condition - unread by the looks of them - rare books are for sale for just £85.00. Seldom seen complete for sale as a full-set.

Please email me here if interested: enquiries@jamesbondfirsteditions.co.uk

These are the books that broke Fleming’s intentions

There’s one very good reason these paperbacks are oddities in the world of James Bond.

It was Fleming himself who famously said in a TV interview that his often sex/violence-laden novels were written for: “Warm-blooded heterosexual adults; you know, in beds and aeroplanes and railway trains. They are not meant for schoolboys.”

But school-boys clearly ‘were’ reading his books, and no doubt for many of these adolescents, Fleming was their first exposure to sex and crime.

Given this reality, somewhere along the lines, it prompted seven specially-adapted titles to be made that were earmarked specifically for children’s eyes – perhaps created to prevent them reading (and being corrupted by), the actual novels.

They were first published by Hutchinson & Co in the 1970s (with Casino Royale actually the last to be printed in 1978), and were in print well into the 1980s.

Although print runs aren’t know, what I can say, is that while one or two of these titles occasionally pop up, as a complete collection, these books have now become somewhat elusive to find (especially in the very good, practically unread condition these are in).

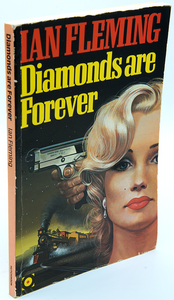

The full set comprises Doctor No (with Dr this time spelled out in full), published in 1973; Live and Let Die (1975); Goldfinger (1976); The Man With The Golden Gun (1976); On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1976); Diamonds Are Forever (1977) and Casino Royale (1978).

These were the original redacted/re-written Fleming novels

What I find interesting about this set in particular, is that a long, long (long) time before we had the recent furor about Ian Fleming Publications republishing the Bond books under their own imprint and having been checked by ‘sensitivity readers’, these paperbacks showcase a set that were the very first to be full-scale and significantly bowdlerized.

What’s also worth noting is that in reality, the changes by IFP only really amount to the odd word being changed.

By comparison, these paperback books are significantly cut down for young readers’ eyes – being significantly shorter, and substantially re-written (by Patrick Nobes), as a result.

Dr No’s 256 pages (in the original Jonathan Cape hardback), for example, downsizes to a much more slim-line 118 pages in the Bulls-eye edition, with similar cut-downs recorded for the other books.

In the Bulls-eye version, for example, The Man With The Golden Gun comes to a very malnourished-sounding 124 pages (compared to the 221 Cape pages); On Her Majesty’s Secret Service bows out at 127 pages (vs 288); Live and Let Die halts at 128 pages (vs 234); Casino Royale is 127 (not 213); while Diamonds Are Forever is 128 pages long (against Cape’s 257). Goldfinger – by far the longest Fleming book, at 318 pages for the Cape original – gets cut down the most, loosing nearly 200 pages of text, coming in at just 127 pages in the Bulls-eye version.

Some things stay, and some things go

But what’s really fascinating from a reader’s point of view is how these books were cut and re-worded, including seeing what was left, and what was ultimately removed to protect young children’s minds.

Because there are some surprising findings.

The dramatic final paragraph in Casino Royale, for example, is one that particularly stands out.

Featuring Bond calling in to station HQ, he delivers one of his most famous lines - ‘The bitch is dead now.’

Strangely, in the ‘young’ readers’ version, this line remains completely the same. The only bit that did change was Bond saying ‘It’s an emergency’ in the original, to ‘It is very urgent’ (which actually reads far more clunkier). Of all the parts of the final paragraph, it’s the expletive that is kept, and a rather innocuous line that’s changed instead (and badly at that). That's very surprising to me!

Obviously, with seven books, it’s entirely possible to write a separate opus for each of the books, on the differences between the original and the young readers’ versions, but what strikes me is that – across the board – the adaptations don’t seem to follow very hard and fast rules across the series. Some things go, but some seem to stay, and there's no consistency about it.

Take Dr No. It is in the Cape book (Chapter 8 ‘The Elegant Venus’), where we are first introduced to Honeychile Rider - described as ’not quite naked’ but wearing a belt around her waist that ‘made her nakedness extraordinarily erotic.’

Fleming adds: 'She stood in the classical relaxed pose of a nude…'

In the Bulls-eye edition, not only does her entrance not appear till chapter 14 (all the paperbacks introduce many more, shorter chapters – this book has 35 compared to Cape’s 20), but her appearance to Bond has been very much edited.

It reads: “Standing on the beach, with his back towards him stood a girl. She wore only a broad belt around her waist…her figure was beautiful.”

As you can see, no specific mention of nudity or eroticism. But it’s odd that ‘bitch’ from Casino Royale survives, but any suggestion of nakedness does not!

Yet, in the final chapter – ‘Slave time’ in the Cape – despite the chapter becoming the much more innocent-sounding ‘At home with Honey’ – the ending (the pair having sex), is still very much implied.

In the Bulls-eye book, it finishes: “He got up and went round to where she was sitting. He kneeled [sic] down beside her and took her hand and kissed it. He felt her other hand on his hair. Slowly she pulled his head to her. Her body smelled of new-mown hay and sweet pepper. “You get plenty to eat in Kingston tomorrow,” she said. “Tonight you can prove to me that you love me. “But Honey…” Bond started to speak. Honey stopped him. “Do as you’re told,” she said.” (The End).

To me, this still sounds quite sexually charged, and as many will know from the Cape edition, it’s very similar to what Fleming originally wrote. Yes, the part where Honey starts undressing herself, and signaling the passion about to ensue has been removed in the paperback [as is the line: ‘under the pale moonlight she was a pale figure with a central shadow…she undid his shirt, slowly and carefully.’].

But thereafter we see a familiar line: “Her body, slow to him, smelled of new-mown hay and sweet pepper.” At this point they clamber in a sleeping bag, suggestively described as having a ‘mouth laid open’ – which isn’t in the paperback – and then we have the similar ending – “You promised. You owe me slave-time. ‘But…’ ‘Do as you’re told.”

OK, so it’s not quite the same, but there’s enough elements I think to raise the pulse of the average 13 year old boy – not least Bond being told by Honey to do as he’s told!

In the other books, there is similar variation of editing.

Live and Let Die – the most obvious example (and the one that most suffered the fate of the sensitivity readers at IFP), is worthy of attention.

To start with – and surprisingly – it (slightly) more closely resembles the original Cape when it comes to chapter names and numbers of chapters. Here the Bulls-eye editors have upped the number of chapters from Cape’s 23 to its 33, but many of the original chapter names survive (The Big Switchboard, Bloody Morgan’s Cave; Table Z, Mr Big; The Everglades; Death of a Pelican; He Disagreed With Something That Ate Him; Goodnight To You Both; Terror by Sea, Passionate Leave etc.). The rest are new fill-ins.

Between the chapters entitled: The Big Switchboard and Table Z is the infamous ‘Nigger Heaven’ chapter from the original Cape, that in the Bulls-eye book this becomes ‘The Boneyard’ – but there are still plenty of references to ‘The Negro’, and much of the description and characterisation of the black mobster characters remains.

Moving on to 'Table Z' - this is the chapter where the oily, glistening, sultry dancer 'G-G' whips everyone up into a frenzy, leaving the audience ‘panting and grunting like pigs’ (a line that I believe is removed from the new IFP books).

In the original Cape book, Ian Fleming goes into much more sexualized detail about the dance, and its slow build to the crescendo which the paperback leaves out. But the paperback still has a go at condensing the scene, and would, I think, still excite its young-blooded readers.

In the Cape we see the passage: “She was naked except for a brief vee of black lace and a black sequin star in the centre of each breast. Her body was small, hard, bronze, beautiful.” In the paperback, it becomes: “Her body was small and slim. Her black skin had oil on it and shone in the light except where two silver stars and some black lace covered her.”

Thereafter, Bulls-eye readers are treated to a shorter summary of the dance, where “her whole body began to shake. Her stomach went round and round, in and out…The sweat shone on her stomach and breasts . Her body began to jerk faster and faster. She let out a scream [the crowd] grunted and panted.”

But the Cape reads similarly: “Her belly moved faster and faster. Round and round, in and out…The sweat was shining all over her now. Her breasts and stomach glistened with it. She broke into great shuddering jerks. Her mouth opened and she screamed softly…. Bond could hear the audience panting and grunting like pigs.”

What’s clear from comparing the two Live and Let Die books is that much of Fleming’s adult padding-out detail of the Capes is removed, but the very necessary bits that are needed to not deviate from the story still remain in the paperbacks. What's more, I would argue, that considering these books are for young minds, the thresholds for what stayed and went still have you puzzled.

Live and Let Die ‘could’ certainly have been toned down more, but the decision to leave substantially some of the key sexual element is obvious.

Dealing with race

In other books we know there is other racial stereotypes used.

What some regard as racial slurs/stereotypes feature heavily in the original Cape Goldfinger – not least where the the entire Korean people (of which Oddjob is one), are described as being “the cruelest and most ruthless in the world.” Oddjob's cat-eating tendencies are also revealed.

In the Bulls-eye book, Goldfinger tells Oddjob that he may eat a cat for dinner, but the racial generalisation is significantly toned down, to read: “This Korean [ie singular, describing only Oddjob rather than an entire race], is one of the most cruel men in the world.”

The above examples are just some of the main differences that are possible to explore.

Other obvious passages could include an infamous one from The Man With The Golden Gun (Cape) describing ‘Pistols Scaramanga’ as most likely be be a homosexual because he can’t whistle (a popular-held view at the time).

This is not included at all in the children's paperback (see image above), nor is any mention of his ‘golden gun’ perhaps being used as a totem of his sexual deviancy.

I wonder what the editors would have done with the very infamous ‘all women love semi-rape. They like to be taken’ line from The Spy Who Loved Me – which wasn’t (perhaps fortunately), turned into a Bulls-eye edition. This book was criticised as being the most sexually-charged book of the lot.

If you want to explore more of these interesting differences yourself – you can. This set is for sale, as a combined set (rather than me selling them individually).

What we can learn

At a time when people’s sensitivities seem heightened, and at a time where Bond is sometimes described as not suited to modern social norms [unfairly in my opinion, as the books are simply ‘of their time’] – these children’s versions are an interesting insight into what editor (censors?) thought was and wasn’t acceptable to children in the 1970s.

For this reason alone, I think this set of books are interesting.

They’re interesting in how they’ve dealt with the very adult prose of Fleming, and attempted to make it suitable to young children (not necessarily always successfully I would say).

The very existence of these books (I feel) is odd – given Fleming never intended his books to be read by kids.

But kids versions they clearly became. They reflect the 1970s view of what kids could handle (just ten years on from the very last book).

And here’s a thought: I would argue that what the kids were given then was far more pithy than what some ‘snowflake’ readers would like to see done to the Ian Fleming books today.

If you would like to add this set to your collection, do let me know.

Some more images below.

All the books are in near-fine and (from what I can tell), unread condition. No internal marks, writing or blemishes, with un-cracked spines.

A really rare set to get, especially in this condition.