Deciphering Fleming: Proof copies (pt 3)

- Peter Crush

- Jun 11, 2025

- 12 min read

It was branded the most salacious book of the series so far, and was later disowned by even Fleming himself - so surely the uncorrected proof edition of The Spy Who Loved Me is rife with lots of textual differences compared to the final published book? Well...perhaps not!

Above: The proof edition of The Spy Who Loved Me - limited to around 500 copies only

In February 1961, from his home in Goldeneye, Jamaica, Ian Fleming wrote to his publisher – as he customarily did at around that time of year – to inform them on the progress of his latest James Bond novel.

“I have done about 25,000 words,” he proclaimed. “…written by a 23-year old girl! No idea if it will come off,” he continued ebulliently, “and I doubt it will go to more than 50,000 words (not copies). So look out your thickest rag paper, and your fattest type.”

As letters to publishers go, Cape’s marketer (and later chairman), Michael Howard must have been wondering precisely what he was shortly going to be receiving.

Fleming was right when it came to word-length. The finished book stretched to just 42,340 words – making it officially the shortest Bond novel – even slimmer than Casino Royale. And despite Howard later writing that the ‘experiment’ (as Fleming called it) – to write this novel in the first-person, from the perspective of the book’s heroine, Vivienne Michel, was “1000% successful,” perhaps, deep-down, he really knew what Fleming later thought of this 9th book in the series – that it was an experiment too far. For although a first edition print-run of 40,000 copies was instructed at the end of October 1961, by 10th November, this had already been reduced to 30,000.

Cape’s fear that this novel wouldn’t land well with readers expecting the traditional Bond formula was ultimately proved right, when – after receiving the first of the bound up uncorrected proofs in December 1961, the editor of Today magazine declined to serialise the novel – perhaps owing to its overly-sexualised content. And although the book did run to four impressions within its first seven months (the most frequently reprinted book until On Her majesty’s Secret Service, which had five in its first year), Fleming later acknowledged that his experiment had “obviously gone very much awry.”

In fact, such was the reaction in some quarters (it was banned in Australia – over issues around sex and abortion), that he specifically requested no further hardback reprints be made; that the paperback edition be scratched; and that no element of the storyline appear in any films [Requests that were rowed back on, especially after his death in 1964, when publishing paperbacks and hardbacks resumed].

The uncorrected proof...

So what can the uncorrected proof tell us about this eventually disliked book that Ian Fleming had initially written with such optimism?

Was the original uncorrected proof version even ‘more’ salacious – such that it needed significantly toning down? Or was this version substantially based on the already editorially corrected typescript that was ready as early as 27th July 1961, and was the version initially send to Viking Press in September of that year?

And what about that most famous (and controversial) of lines – “All women love semi-rape…”

Well, there definitely ‘is’ something to say about this.

But more about that later!

First thing’s first: What we know:

Before going into the detail, there are some initial things that we already know about this specific uncorrected proof.

Firstly, what we do know for a fact [See Gilbert], was that for The Spy Who Loved Me, there was a very short proof-reading/editing window between the first softcover proofs being ready (around 15th December 1961), and the first hardcover copies being bound up (by end of January 1962).

Take-out the two weeks of Christmas, and that’s not much time to give the book a very thorough read.

What we also know (and this is certainly what I’ve found in my other assessments of proof Fleming's), is that typically, the Fleming uncorrected proofs seldom reveal anything significant than beyond standard typos, grammar errors, spelling errors or those made for typographical layout reasons (such as bad-breaks in words split over two lines, or consecutive pages).

In fact, the only example I’ve so-far seen of a big story detail being changed between the proof and the eventual trade release was in for You Only Live Twice (at the end where Bond is floating away on Blofeld’s balloon – see here).

Another fact we know is that for this specific book, Fleming had already made his own corrections during the summer of 1961, and had sent the transcript to a certain Fritz Lieber – a librarian working at Yale – who previously helped proof-read Thunderball, and who here, helped with the ‘gansterese’ vernacular and Americanisms used by the hoods who took over The Dreamy Pines.

So… with all this in mind, just how polished a book do we think this was by the proof stage?

Well, I’m going to stick my neck out and say that of the proofs I’ve looked at so far, The Spy Who Loved Me (despite it potentially being the one that could have still needed to be toned down the most), is, in my opinion, one of the more ‘finished’ examples [in terms of how the proof compares to the finished book] that I’ve seen.

I went straight to the most obvious parts of the book – for instance where Vivienne is engaging in foreplay whilst in a private box in a cinema in Windsor, to where she eventually had sex for the first time – and I couldn’t see a single word, or phrase, or few words changed – at all.

Of all the places I thought an alteration might still have been needed (perhaps to assuage any potential backlash – including references to breasts being touched, penetration etc.) – there were none at all. I can only conjecture that Fleming knew what he wanted to say, and by proof stage, what was in, stayed in.

I say this, because it’s not as if lots of small little details changes weren’t being made at this point.

As Gilbert spots in his assessment of the proof, odd phrases were still being tinkered with.

In the proof, on p17, for example, we have the reference to “sudden gusts” [of wind].

But narrative flourishes were still clearly being added, as on the final first impression, it had been turned into a more Fleming-esque and evocative “angry gusts.” (See below):

It seems that for arguably less memorable parts of the book, small tweaks were still very much being made, but around the central, key sexually physical moments, no such changes were being made or were allowed to be made (perhaps because these were parts already deemed to be as the author wanted).

No differences also exist between the uncomfortable pages around pp74-78 where Kurt packs Vivienne off to Zurich to have an abortion (which was still illegal in the UK at the time).

An army of editors?

According to Gilbert, the proofs were sent to a number of different "editors and production department" staff at Jonathan Cape, and having looked at my proof, I’m genuinely left wondering whether specific proof readers were tasked with looking for doing things – such as one for spotting literals/typos, while another might have been responsible for scanning the book and ensuring continuity.

Why do I say this? Well, because in my proof copy, it's actually marked up. But, apart from small crosses at the start of each new chapter to denote the need to change them for the more floral initial caps in the finished book (see later), this proof reader has only made two marks in the margins across the entire book.

One is here inserting a ‘to’ - see below:

Above left - missing the 'to' - middle the proof reader's mark - right: the corrected trade copy

The other is a typo on p20 – a proof readers’ mark asking for ‘seem’ to be changed to ‘seen’.

These are clearly not the only changes, but they are the only typos changes this proof reader marked, and potentially they are the only big typos (save for one – see later), because the only other changes that Gilbert mentions are for entire words being changed (as per ‘angry gusts’ and and a clutch of mistakes on pp101 and 102 where some pretty big calendar chronology mistakes are cleared up.

So, maybe one proof reader – maybe Fleming himself – was finessing the descriptive elements, while another was checking dates (and maybe place names - or basically ‘facts’), while another was checking for typos (maybe the reader who had my proof)?

This could make sense, given the short proof-reading time-window.

When it comes to the chronology changes mentioned above, these were fairly big ones that did definitely needed correcting. In the final bound up first impression Vivienne explains that “on the eleventh” [of October], the Phancey’s would be leaving the motel “on the thirteenth”, and she was asked: “would I mind staying in charge that night and handing over the keys…around noon on the fourteenth.” This all makes perfect sense, as on the first opening page (turning onto the second page of the book), Vivienne is starting her story, saying she’d been “running away” and now it was Friday 13th (a good apocryphal date for her ordeal to soon begin on).”

On the proof however, even though it too mentions that it’s Friday 13th on the first few pages, by 101-102 of the proof, it says that on the “on the twelfth” the Phanceys tell her they’ll be leaving on the fourteenth, and would she mind staying 'that' night, and giving the keys back on the fifteenth. In other words, the whole story has shunted forward a day by p101. This doesn’t fit with the opening page, and this is something that was clearly changed by the time the first edition proper came out.

But, this hasn’t been marked up on my proof.

It was clearly marked up on one of them – perhaps by a fact-checker proof-reader. The fact there was actually a real Friday 13th in October 1961 meant that p101 had to be changed, and it was picked up by a sharp-eyed sub-editor.

Other mistakes – which Gilbert also notices – include literals. In the proof, ‘The Dreamy Pines’ was written – on at least three occasions – without its correct capitalized ‘T’ for ‘The’ on pages 11, 26 and 91. This wasn’t wasn’t marked up on my proof either, but the first time this mistake happens is on the very first page of the proof!

Obvious differences first

It should be noted that there are some very evident differences that don’t need too much attention to spot. In the early pages, there is a ‘holding page’ for where the illustration of The Dreamy Pines will be inserted. In the proof it simply says “MAP OF MOTEL TO COME”.

The contents page is also different in a number of respects. Unlike other proofs (such as On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, which use dummy page numbers), the page numbers for each chapter are correct (and as they appear on the trade first impression) – another indication that this was a much more finished book (even at the proof stage) – with no significant changes that would knock out the numbering off. See below:

Above: The contents page on the proof (middle photo), compared to the first trade edition

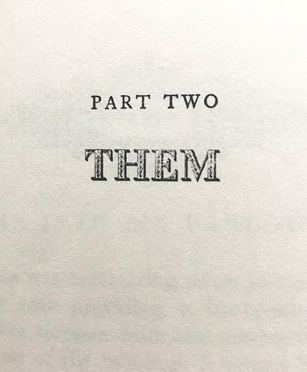

If you notice, on the proof, the contents page doesn’t show that the book is split into the three parts that the finished book is (‘Me’; ‘Them’ and ‘Him’). But an allowance has clearly been made for this, because the page numbering on the proof has already accounted for a title page for each part to be inserted, without upsetting the existing contents numbering.

A visual design difference (lack of finished typeface), is one that we see throughout the proof, and it starts on the title page (see above, compared to the trade edition to the right).

You'll notice the proof doesn’t have the ornate ‘The Spy Who Loved Me’ lettering to the title page that the finished book has. This same ornate lettering features (on the trade edition), as an initial capital letter starting each new chapter, but again, this isn’t on the proof either (see below). It just has a large capital letter that will be replaced by the more ornate one.

Above left: The proof is missing the ornate initial-cap. Above right, as it appears on the 1st ed.

At least there's consistency though. While the proof has each of the ‘Me’, ‘Them’ and ‘Him’ title pages, the lettering is - once again - not in the finished font yet - see below:

What else?

An other interesting oddity about the preliminary pages, is that on the title page on the proof, there is no ‘dropped quad’ – indicating that the dropping of the quad must have happened during the production of the finished books, and not during the printing of the proofs.

Another difference is that - on the proof - there is no “Vivienne Michel writes:…” page - the page that proceeds the list of previously published books and title page spread (see below, left) on the final trade edition.

There is no decorative swirl at the very end of the book either. (See below, middle and below, right).

Gilbert notes that the proof is “an entirely separate typesetting from the published hardback.”

Above: No 'Vivienne Michel writes...' is in the proof. Plus there's no decorative scroll either

One thing is constant though...

Interestingly though, all of the Tetris-style 3D boxes that form a triangular shaped title header (see above right), ‘are’ in the proof.

That’s one piece of the finished design that is already locked in by this point.

…and... the line about ‘semi-rape’?

Don’t worry, I haven’t forgotten about this!

Perhaps one of the most often-talked about lines in all of the Fleming books came from this book – the line that reads “All women like semi-rape. They like to be taken.”

[It’s a line often thought to be reflective of Fleming’s own sadomasochist tendencies].

Well – of all the places where there was an error in the proof – this was it!!

Much like how I revealed that a very famous line from On Her Majesty’s Secret Service [“it’s all right…” – after Tracey had been murdered] was very nearly printed “I,’s all right…” (ie missing the ‘t’ as it existed on the proof) – a similar mistake appears on the proof of The Spy Who Loved Me.

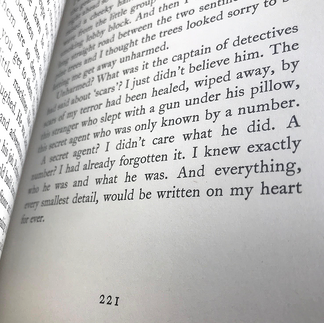

Instead of reading “All women love semi-rape. They like to be taken…” (as it’s supposed to, and does actually appear on the proper first impression), on the proof there is a fundamental error:

On the proof, what we have is a missing ‘y’ making ‘They’ read ‘The’.

I personally noticed this error straight away, although it’s potentially understandable to see why this might have been missed, as a ‘the’ could conceivably been used – to infer that the love they have to offer is being taken more forcefully.

However, it is wrong, and quite obviously, it was changed, and reinstated with what I believe is the correct word, ‘they’.

But, just as the ‘It’s all right…’ line could have very nearly been butchered if left unnoticed in the proof of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, this standout line could also have been left very different.

As with the mistake I spotted in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, this ‘They/the’ mistake wasn’t noticed by Gilbert (it wasn’t in the bibliography) – so I believe I’m once more the first to draw attention to the rather big typo that’s in this book too.

It’s a typo that – had it remained – could have altered how we talked about this particular line.

PS: Isn’t it also strange that these mistakes always seem to appear on what seems to be very momentous lines in a book? [Or are they only momentous in hindsight?]

Conclusions

What I hope to have shown you in this analysis of yet another uncorrected proof, is that there is still much to learn and to be intrigued about when it comes to understanding the writing process of Ian Fleming.

Here we see how obvious changes were wanting to be made – quite late into the editing process – and how big typos could almost have been missed.

I’m personally staggered that certain descriptive words were still being substituted for others - so late on - and I’m pretty sure, that if I went through each page line, by line I could spot more instances were different words were chosen from those in the proof.

It forces so many questions:

Why were these changes deemed to be imperfections – so close to the publishing date?

How personally-involved was Fleming in sanctioning them?

My guess would be that Fleming was very involved.

But why was the text still being so minutely tinkered with? Does it reveal a quest for perfection right up until the last moment?

These are questions that we will no-doubt never get a full answer to.

But I like the fact that long after the initial type-written pages were re-typed, edited, and type-set, it was still deemed necessary to add in last minute details, or adjectives that would just maintain the zest/pace of the novel.

The Spy Who Loved Me might well have be one of Fleming's most disliked books, and it's certainly one of the most under-appreciated books by Bond fans, but it was still being fine-tuned, right till the end. And you’ve got to give Fleming credit for that at least.

Comments