Deciphering Fleming: Proof copies (pt 4)

- Peter Crush

- Sep 19, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Sep 21, 2025

The Man with the Golden Gun was the most unfinished novel - does the proof also show this?

When the curtain finally came down on the last of the full length Ian Fleming novels in 1965, with the release of The Man With The Golden Gun, most James Bond fans will probably agree that despite huge posthumous sales, the series ended with something of a literary whimper.

Here was the publication of what many regard to be a half-finished novel, only barely knocked into shape by Kingsley Amis (although debate still exists about the true level of his involvement) - see later.

By Fleming’s own admission, he felt that by this 13th book, he had “run out of puff and zest.”

So, despite the first draft being finished before Ian Fleming’s death (and handed in to copy editor, William Plomer), much of the detail that Fleming normally added in the second draft was never added. Even though some sources say Fleminghad corrected “the first two-thirds of the book” by May 1964, other reports suggest that Fleming told Plomer the book was not fit for publication. What is fact, however, is that by August that year Fleming was dead.

In fact, it’s precisely because the finished book does appear so ‘unfinished’, that it’s given rise to the theory that Amis’s suggestions for polishing the manuscript were not actually adopted, and that the book was largely published as it stood, ie how it was left by Fleming himself.

This theory is strengthened by a review of the book by (a perhaps scorned), Amis himself, who said the book was “a sadly empty tale.” He also drew particular attention to weaknesses in the novel, including questioning whether these demonstrated that parts of the original text “could have done with more work.”

Gilbert’s own analysis says that although Fleming was involved in part of the typescript stage, “The Man With The Golden Gun did not undergo such meticulous revisions by the author in typescript, and the majority of the corrections were carried out by others.”

Indeed, when sending out batches of pages, Fleming’s secretary, Beryl Griffie-Williams, added a note to Fleming’s typist Jean Frampton to: “please be very kind and do your usual corrections… Mr Fleming has not been too well, and consequently has been unable to face the corrections.”

The Proof

So, how exactly does all this irregular build-up to the final novel affect the state of the uncorrected proof? Does it contain clues as to just how unfinished this book really was?

As my previous blogs have attempted to demonstrate, many of the uncorrected proofs I’ve seen still contained many errors – some significant, and some even requiring entire passages to be completely changed for the final book in order for plot details to make sense. I’ve found a hitherto in-written about passage in You Only Live Twice, for example, that wasn’t just a corrected typo, but comprised large differences in how Bond escaped Blofeld’s island of death (and still needed changing for things to make sense - read more about this here).

So did the fact that the original typescript of The Man With The Golden Gun was so incomplete mean that substantial differences remain in the proof compared to the final book – or was the book so unfinished in the proof, that it wasn’t deemed possible to really start playing around with it by this late stage?

These are interesting questions I feel. What we do know from Gilbert, is that the final typescript was ready by September 1964 – a month after Fleming died – but the uncorrected proofs were not issued till ‘late 1964’ and only ‘distributed in the New Year’.

This means anyone reading the uncorrected proof would not have had long to make known any of their corrections. Why? Well, Gilbert also notes that the first bound copies of the finished trade edition were delivered to Cape in February 1964 – meaning that there was only a very short window of maybe 3-4 weeks after the proofs had been made available to read before the book was then off to the printers.

Immediate differences:

Before delving into the text, there are some immediate design differences that can be seen.

The contents page (see picture above), doesn’t have dummy numbers (at least one of the previous proofs – On Her Majesty’s Secret Service – does), suggesting that the book was considered complete enough for there not to be any worries that new corrections could impact pagination, or drop the text onto a new page.

There is another immediate difference too. On the proof (see above), there is a vertical ‘line’ built into the design of each new chapter page – with there being a chapter number to the right of the line if on a right hand page, or to the left of it if the new chapter started on a left-hand page. (This line also appears on the contents page).

If you look at the two images above, (proof on the left, final trade edition on the right), we can actually see how this line, and chapter number design rule clearly caused some confusion with the designers. For on the proof, Chapter 4 (a left-hand page-starting chapter still has the line and the chapter number to the right of this page, instead of being to the left of the chapter head – as corrected in the final book – see above, right.

As can also be seen in the images above though, this line is very long on the proof, but it’s been cut down to size considerably on the final trade edition. The shorter line doesn’t change the blocking – there is still the same number of lines to be page – set in the same area. It’s just that the ‘line’ doesn’t extent so high into the margins on the final trade edition. On the contents page of the finished first edition, this line disappears completely. (See below):

The text:

So what can we deduce about the completeness of the book (textually), by the time the uncorrected proof is ready?

There is an immediate ‘error’ that I would say exists on the second line of the very first page – in which the Secret Service is described as an organisation - spelled with a ‘z’ rather than an ‘s’. Given that other words in the book have not been Americanised, then I would regard this as an oversight.

Gilbert, in his biography, spots lots of the same errors I’ve also spotted – but the conclusion I find myself coming to is that it’s the sheer number of ‘basic’ typographical mistakes compared to other proofs I’ve looked at that suggests the proof book really was (still), the unfinished product.

More than other proofs, this proof is much more riddled with errors of the basic typos type – mostly in the form of missing, or wrong letters.

For instance, we see ‘Mr Emm’ (phonetically describing ‘M’), using two mm’s (found twice in the proof), when it should be ‘Mr Em’ (ie one ‘m’) – which was spotted, and corrected in the final book.

(If you look really closely below (where the yellow arrow is), I think you can even see a very feint pencil mark on the proof where this mistake area has been highlighted):

But to me, this proof stands alone in terms of the number of ‘silly’ mistakes.

In particular rather than typos or misspellings, we seem to see more than our fair share of missing letters – for instance, we see ‘who live’ instead of ‘who lived’ (p42) - see below:

A missing ‘d’ is again seen on p27: ‘solve by a killing’ instead of ‘solved by a killing’.

It’s an ‘ed’ missing on p85 (‘He paused and add’, instead of ‘He paused and added’) – while on the very same page, we see another missing letter: ‘Care to earn yourself grand’ instead of ‘Care to earn yourself a grand’ (ie a missing ‘a’).

To have two such elemental errors on the same page really does suggest rushed typesetting and a failure to observe attention to detail. On another page, we even see a ‘cf’ used instead of ‘eg’!

These quite basic mistakes really do look like they’re straight from a typescript – mis-typed words/phrases, reproduced and uncorrected.

And as I say, there does just feel like there’s a lot of them.

Another awkward line is this one:

‘007 was a good agent once’. (see pic left)

Starting a sentence with a number is typically a grammatical no-no, and even though 007 is Bond’s ‘code name’ (and so arguably excusable), it still sort of looks odd.

It’s still there on the final Cape first edition (on p32), along with another sentence that starts with ‘007’ on the same page (‘007 was a sick man’).

I'm not an expert, and I can't recall if other titles start sentences in a similar fashion, but as I say, even though it may be correct, it still looks wrong. Indeed, it's not as if a spelled-out solution could have been used instead. In fact, later in the trade edition of The Man With The Golden Gun there are mentions of his name – but this time spelled-out [on p32 there is a line that talks about ‘his Double-O’ prefix’ (and also with a letter ‘O’ this time not a number zero).

Just one real biggie

Apart from these and many more basic errors, there’s one really long passage that is substantially different in the proof compared to the final trade edition.

But, unlike the passage I revealed in You Only Live Twice – where the change was needed to fix elements that were implausible and didn’t match earlier references in the book – this time, it’s not really clear ‘why’ this rather substantial change was made.

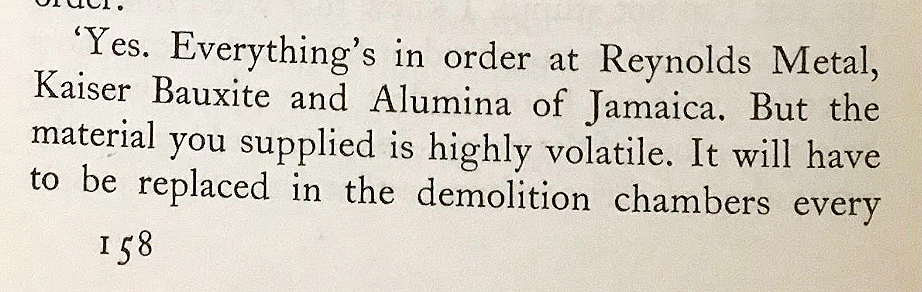

Here it is below on the proof – the section in question is at the bottom of p158 and carries on to the top of p159:

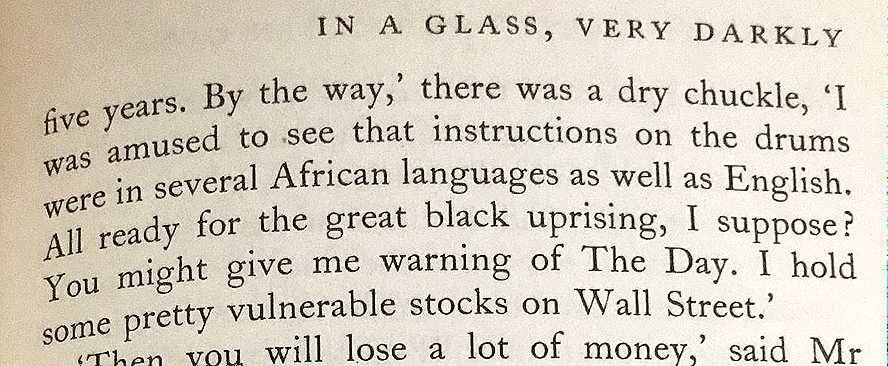

On the proof it reads: “Yes. Everything’s in order at Reynolds Metal, Kaiser Bauxite and Alumina of Jamaica. But the material you supplied is highly volatile. It will have to be replaced in the demolition chambers every five years. By the way,’ there was a chuckle, ‘I was amused to see that instructions on the drums were in several African languages as well as English. All ready for the great black uprising, I suppose? You might give me warning of The Day. I hold some pretty vulnerable stocks on Wall Street.”

In the corrected trade edition it’s been changed to (differences in red):

“Yes. Everything’s in order at Reynolds Metal, Kaiser Bauxite and Alumina of Jamaica. But your stuff’s plenty – what do they call it? – volatile. Got to be replaced in the demolition chambers every five years. Hey,’ there was a dry chuckle. ‘I sure snickered when I saw that the how-do-it labels on the drums were in some of these African languages as well as English. Ready for the big black uprising, huh? You better warn me about The Day. I hold some pretty valuable stocks on Wall Street.”

As re-writes go, it’s fairly substantial, but why?

It mainly looks like tinkering for the sake of it (chuckle changed to ‘dry chuckle’, and ‘several African languages’ is changed to ‘some of these African languages’).

We see ‘the great black uprising’ watered down to the ‘big black uprising’ (but still ‘big’), and then there’s the passage where ‘instructions’ get turned into the more explanatory ‘how-do-it labels’ – but I would argue it’s simpler as it originally was.

Continuing, on the proof we see: ‘But the material you supplied is highly volatile’ has now been turned into ‘But your stuff’s plenty – what do they call it? – volatile.’

But, again – is this necessary? Does it actually add anything?

And what’s possibly more pertinent – exactly ‘who’ was making these larger changes (it certainly wasn't Fleming, he was deceased) – and on who's authority did the person doing this have to make changes that are much more substantial than just mere typos?

I somehow doubt these questions will be answered.

What I do know is that The Man With The Golden Gun remains a curious book.

In certain passages, it reads awfully unfinished, devoid of the usual Fleming detail that is on the one hand, so minimal and yet is so noticeably absent when it’s not there.

Yet, elsewhere in the book, there are entire passages that could be considered classic Fleming. These passages look finished, complete, complex, and done with the author's uncanny ability to say lots but with the most efficient use of language. Take this first page of chapter 3, for example, one that I would argue is as deeply descriptive and any other Bond novel:

So how do we judge this uncorrected proof?

Substantially the book 'is' all there. Sections I gave close attention to, that I felt might have changed between the proof and the final trade edition (such as when Scaramanga is first introduced, with all his characteristics), were all word-for-word the same.

The ending is the same too - a rather bittersweet ending I've always felt - and big changes there are 'not'. So in this way, this proof differs very little from the other proofs.

But what I will say, quite conclusively, is that this uncorrected proof (much more than others I've seen), is simply littered with the sorts of errors that a first stab at the typescript should have ironed out even before being bound up as the proof.

As it stands, the uncorrected proof of The Man With The Golden Gun does little to convince me that this wasn't rushed affair.

The real miracle is that these typos ‘were’ actually spotted, and remedied in such a short space of reading time.

But here's one, last final observation - and one which convinces me even further, that this ‘is’ a curious proof.

This is a proof that on the one hand can't spell 'Em' properly, and misses out letters or 'ed's - and contains very basic errors. And yet right at the end, it could corectly spell the word ''haemorrhage' - one of the most infuriating words to get right. Go figure!!

Comments